Spontaneous language creation and the relationship between gesture and speech

In the on-going debate between linguists and psychologists concerning language development in children, a promising line of research has emerged concerning the spontaneous creation of ad hoc sign languages among the genetically deaf members of isolated communities. In at least three documented cases – fishermen in Martha’s Vineyard, children in Nicaragua and Bedouins in the Negev desert in Israel – spontaneous sign languages (SSL) have emerged among people isolated from contact with institutionalized sign languages (ISL). The linguistic characteristics of these SSLs show interesting parallels with, as well as differences from, those of spoken languages or traditional sign languages used in the surrounding communities. They differ from the gestures used by hearing language users to accompany their speech or the spontaneous gestures used by infants between the ages of 18 and 24 months.

Martha’s Vineyard

In a recent article[1], Nora Groce discusses the SSL developed by the non-hearing inhabitants of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, as early as 1700 and used by all the members of the community until the mid-20th century. Unfortunately, there is no complete description of this language, which emerged long before the creation of the American Sign Language (ASL) and of the first American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817. Although it later acquired some of the characteristics of ASL, due to increased interaction between islanders and mainlanders, it remained quite different and modern-day islanders who still remember the language find it difficult to understand the SL used by non-islanders or used to translate speech on television.

Nicaragua

In 2004, Ann Senghas and her colleagues reported a spontaneous new sign language which has emerged among deaf children in Nicaragua since the 1980’s.[2] Until that time, deaf Nicaraguans had little contact with each other and so had no chance to develop a sign language; they used only a few “home signs” to communicate their needs to family members. In 1977, a school for special education was opened in Managua, followed by a vocational school for the deaf in 1981. Enrollment grew rapidly from an initial 50 students to several hundred. This put young deaf students in contact with each other and a rudimentary sign language soon emerged and was developed and perfected by each new generation of students. Interestingly, since new developments came from the younger generation, a novel situation was created whereby language was passed “up” from the younger to the older generation instead of the other way around.

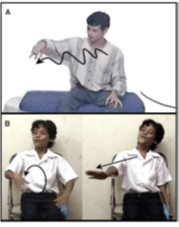

According to the authors, “children analyzed complex events into basic elements and sequenced these elements into hierarchically structured expressions according to principles not observed in gestures accompanying speech in the surrounding language”. This, they argue, is exactly what one would expect from a true language. To test this hypothesis, they asked signers and non-signers to relate events depicted by an animated cartoon to another member of the group, to see what type of hand movements were used to express motion events like “rolling down a hill”. Non-signers accompanied their verbal description with holistic hand movements, termed “gestures” by the authors, to distinguish them from the “signs” used by deaf participants. By “holistic” is meant a single gesture including a rolling movement and a descending movement (A). These were used by all the non-signers and by several of the older signers. Discrete linear movements – a rolling gesture followed by a descending gesture (B) – were used by all the youngest signers but by none of the non-signers.

Figure 1: Gestures used by signers (B) and non-signers (A)

In other words, as the new sign language developed, the distinguishing attributes of language, what Hockett termed “design features”[3], that is, discreteness and combinatorial patterning, emerged among the children, but not among the adolescent and adult signers. This, they argue, “is consistent with, and would partially explain, the preadolescent sensitive period for language acquisition”.

The Al-Sayyid Bedouins

This case differs from the other two in several ways. First, contrary to the Martha’s Vineyard case, the Bedouin sign language was invented in the last 75 years and has been recorded and described in detail, thanks to bi-lingual translators. Second, contrary to the Nicaragua case, this is a language which has arisen spontaneously in a socially stable community. In their study[4], the authors focused on grammatical properties, notably sentence structure, rather than on the nature of the hand movements.

The method

The study concentrated on the second generation of signers, the first having no living members left and the third made up of subjects deemed too young. Two tasks were presented to them:

- Spontaneous narratives given in response to a request to recount a personal experience and

- Descriptions of single events portrayed by actors in a series of short video clips.

The corpus consisted of the responses to these tasks. “Sentences” were identified by the presence of an action or an event sign as nucleus. Constituents were classified semantically as noun (N) arguments, adjectives, numerals, and negative markers, based on the translations. Sentence boundaries were identified through prosodic and manual cues: shifts in the rhythm marked by a pause, lowering of the hands, a change in head or body position, etc. These same cues have been observed in other sign languages.

The following is the analysis of one utterance, represented by five signs: MONEY COLLECT BUILD WALLS DOORS.

The first prosodic constituent is MONEY COLLECT. Based on the translation, it is analyzed as: “I saved money”, with an unmistakable [Object-Verb] construction. This predicate-final order was characteristic of 136 utterances produced by the signers out of a total of 158, which is contrary to the [S-V-O] sentence word order in the Arabic dialect spoken by the Bedouins.

The final three elements could be analyzed in two different ways: either as a predicate, BUILD, followed by two direct objects, WALLS DOORS (Then I built the walls and the doors), or as a sentence containing only a predicate, followed by a list (Then I built the house. The walls, the doors.) The body language used by the signers and the translations given by the interpreters confirmed the latter interpretation: “I saved some money. I started to build a house. Walls, doors.²

When subjects were used, they always preceded the object-verb sequence, thus giving a basic [S-O-V] sentence structure. Both subjects and objects might also remain unexpressed. When adjective modifiers were used, they always preceded the noun, thus giving a head-final structure. These features differ both from Israeli Sign Language and the spoken Arabic dialect used by the non-deaf members of the community. On the other hand, the [SOV] order is the most common order observed across world languages. Further, as observed by S. Goldin-Meadow[5], young deaf children who spontaneously create a sign system without input from either a spoken language or a sign language, consistently produce two-gesture strings with action signs in final position. To quote the authors: “The appearance of this conventionalization at such an early stage in the emergence of a language is rare empirical verification of the unique proclivity of the human mind for structuring a communication system along grammatical lines.”

Gestures versus signs

Hearing children spontaneously produce gestures in the early stages of language learning and hearing adults accompany their speech with gestures. However, as noted above, these gestures differ from the signs used in institutionalized sign languages or invented by isolated deaf children.

Hearing children begin using gestures between 8 and 12 months, first using “deictic” gestures, such as pointing, which are entirely context dependent for their meaning, in other words, you have to look at what is pointed at to understand the gesture. At about one year, they begin using “iconic” gestures, that is, gestures which represent in some way the object referred to, such opening and closing their mouth to represent a fish. At two, children use a wide range of iconic gestures to represent words (tractor, rain), to describe them (hot, hard) or to express how they feel about them (like, dislike). These gestures are used alone at first, then along with words and finally are replaced by words. Gestures clearly serve to “bootstrap” language learning and have been shown to improve comprehension and memorization at all ages.

Adults in all cultures use a variety of gestures to accompany their speech. Are their gestures the same as those used in early childhood, or in spontaneous or institutionalized sign languages? The answer is no. When researchers observed hearing parents communicating with their deaf children, using a combination of speech and gestures, they noted that there was no structure to their gestures. However, when asked to communicate with their child without speaking, they noticed that the parents’ hand movements were more clearly detached and were combined similar to the way deaf children use them. In other words, the core properties of language construction, segmentation and combination, appeared in the parents’ signs as soon as they were forced to communicate without speaking.

Conclusion

The debate on language development in children referred to in the introduction focuses on the “nature/nurture” question, that is, what is innate and what is learned. Since hearing children are constantly in contact with speakers of their native language, it is difficult to distinguish between what they are “programmed” to know and what they learn by imitation. On the other hand, cases of deaf children in isolated communities who invent their own language allow us to see the problem from a completely different perspective. These cases teach us several things. First, deaf children who are isolated from other deaf people as well as from institutional sign languages, remain stunted in their development and only produce so-called “home signs”. In other words, for language development as for many other aspects of human development, it takes two to tango! On the other hand, once two or more deaf children are together, they immediately create a sign system to communicate and these systems seem to possess the same characteristics: segmentation and combination, which are universally considered to be the core properties of language. Likewise, their hand movements are structurally different from those used by hearing people to illustrate their speech. But even hearing people begin to structure their gestures when forced to forego speech. And mothers talking to infants change their gestures too: like the “motherese” they use when speaking their gestures are simpler and more clearly detached.

In my previous article: “L’émergence du langage”, I discussed the possible relationship between non-human communication, archaic human communication and the development of language in children. The growing interest in the scientific community for the study of gestures accompanying or replacing speech has contributed significantly to this debate. Studies of primates have made it clear that, while they can learn and use new hand gestures, it is impossible for them to learn spoken words. The spontaneous emergence of sign languages like those discussed above has led scientists to conclude that our most primitive ancestors probably developed a sign language before or along with the beginnings of spoken language.

[1] “Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language”, Nora Groce, Society for American Sign Language Journal, Volume 4, Number 2, Article 4, September 2020.

[2] “Children Creating Core Properties of Language: Evidence from an Emerging Sign Language in Nicaragua”, Ann Senghas, Sotaro Kita, Aslı Özyürek, Science, Vol 305, 2004: 1779-1782.

[3] C. F. Hockett, Refurbishing Our Foundations: Elementary Linguistics from an Advanced Point of View, Benjamins, Philadelphia, 1987.

[4] “The emergence of grammar: Systematic structure in a new language”, Wendy Sandler, Irit Meir, Carol Padden, and Mark Aronoff, PNAS, February 15, 2005, vol. 102, no. 7: 2661–2665.

[5] “Spontaneous sign systems created by deaf children in two cultures”, Susan Goldin-Meadow & Carolyn Mylander, Nature, 8, Letters to Nature, Vol 391, 15 January, 1998: 279-281.

Laisser un commentaire